Sunday, 24 February 2013

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

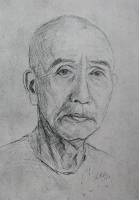

Khoo Hun Yeang 邱汉阳

|

| Khoo Hun Yeang |

Khoo Hun Yeang was born in Penang in 1860 to Khoo Thean Teik. His father was a prominent figure in Penang and Perak. Khoo Hun Yeang was educated in Penang and joined his father's business in coconut plantation in Province Wellesley. He managed the business successfully for 10 years and returned to Penang to assist her father's interest in the Penang Opium and Spirit Farm in which he remained for another 6 years.

Khoo Hun Yeang later commenced business on his own account in Penang under the firm chop Chin Lee & Co., trading in tin and general trades. In 1899 he joined the Singapore Opium and Spirit Farm, and was appointed managing director of the farm from 1902 until 1906. He relinquished his interest in the Singapore farm and went to Kuching to venture in the construction industry.

Khoo Hun Yeang was the Vice-Chairman of the Penang Chinese Town Hall, a Board Member of the Kek Lok Si Temple and the Cheng Hoon Giam Temple (Snake Temple). The main street, Khoo Hun Yeang Road, in which he built in Kuching was named after him. He died in Medan in 1917 and was buried in Kampung Bahru, Penang, at his family burial ground. He was survived by a principal wife Ong Gek Chai (王玉钗), 8 sons, his two elder sons Khoo Siew Jin (b. 1884) and Khoo Siew Ghee were prominent merchants in Singapore.

Tuesday, 5 February 2013

Chan Chew Koon 曾秋坤

|

| Baron Chan, FRCPCH, MBE © Gary Lee; Universal Pictorial Press and Agency Ltd |

Chan Chew Koon was the first Chinese Lord appointed to the House of Lords in Great Britain. Chan Chew Koon or Michael Chan was born on 6 March 1940 in Singapore. He was educated at Raffles Institution, Singapore and studied medicine at Guy's Hospital.

Michael first served as lecturer and pediatrician at the University of Singapore (now National University of Singapore). Shortly after his return to Singapore, in 1974 he continued his studies in Von Willebrand's disease (a study on the symptoms similar to hemophilia) under the supervision of Professor Roger Michael Hardisty at the University of London's Institute of Child Health. In 1976, Michael then posted as lecturer and pediatrician at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (University of Liverpool). He remained for almost 18 years before appointed as the director of Ethnic Health Unit in National Health Service.

Michael was an active social activist concerning the rights of minorities in Great Britain. He was an advisor to the Secretary of State for the Home Department and a commissioner of Commission for Racial Equality, a non-departmental public organisation in the UK which aimed to solve racial discrimination and promote racial equality. Michael also held various important positions in the field of race relations in the UK, and was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire in 1991.

In 2001, he was appointed member of the peerage and became Lord Chan of Oxton in the County of Merseyside. Michael married Irene Chee Wei Len in 1965 and has a son, Stephen Chan and daughter, Ruth Chan. He died on 21 January 2006.

Tags:

Baron Chan,

Chan Chew Koon,

Lord Chan,

Michael Chan

A Pictorial History of the Overseas Chinese: Song Ong Siang Chinese Portraits Collection

One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore

One of the highly sought after reference materials in Chinese studies in the Straits Settlements would be the classical One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore compiled by Song Ong Siang (later Sir). This 602-page book was first published in 1923 by John Murray, London and later reprinted by the University Malaya Press (1967) and Oxford University Press (1984).

One of the highly sought after reference materials in Chinese studies in the Straits Settlements would be the classical One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore compiled by Song Ong Siang (later Sir). This 602-page book was first published in 1923 by John Murray, London and later reprinted by the University Malaya Press (1967) and Oxford University Press (1984).

The objective of the compilation is to document all influential Chinese in Singapore since its inception as a British Colony in 1819. Hundred of Chinese community leaders, merchants, politicians, etc. are discussed in an anecdotal flow beginning with the history of Singapore as a British Colony. The stories of the Singapore Chinese business interests and contributions to the development of early Singapore are embodied in this book. There are over 100 Chinese individual portraits and family photographs featured in this hard-bound book.

Below is the list of individuals with their portraits featured in the book.

- Boey Ah Sam

- Chan Kim Boon

- Chan Sze Jin

- Chan Sze Onn

- Chao Kim Keat

- Cheang Hong Lim

- Cheong Ann Bee

- Cheong Chun Tin

- Cheong Swee Whatt

- Chia Ann Siang

- Chia Guan Eng

- Chia Hood Theam

- Ching Keng Lee

- Chao Chuan Ghiok

- Chao Giang Thye

- Eu Tong Sen

- Foo Teng Quee

- Gan Eng Seng

- Gaw Boon Chan

- Goh Hood Keng

- Goh Lai Hee

- Hoo Ah Kay

- Hoo Ah Yip

- Hoo Keng Tuck

- Kiong Chin Eng

- Koh Eng Hoon

- Koh San Hin

- Kow Soon Kim

- Kum Cheng Soo

- Kung Tuan Cheng

- K.Y. Doo

- Lee Cheng Yan

- Lee Choo Neo

- Lee Choon Guan

- Lee Hoon Leong

- Lew Yuk Lin

- Lim Boon Keng

- Lim Chwee Leong

- Lim Han Hoe

- Lim Ho Puah

- Lim Keng Kiat

- Lim Koon Yang

- Lim Kwee Eng

- Lim Leack

- Lim Nee Soon

- Lim Peng Siang

- Low Ah Jit

- Low Boon Pin

- Low Cheang Yee

- Low Kway Soo

- Low Peng Yam

- Michael Seet

- Ng Sing Phang

- Oei Tiong Ham

- Ong Ewe Hai

- Ong Sam Leong

- Ong Tek Lim

- S.C. Yin

- Seah Cheng Joo

- Seah Chiam Yeow

- Seah Eng Choe

- Seah Eu Chin

- Seah Liang Seah

- Seow Poh Leng

- Song Hoot Kiam

- Song Ong Joo

- Song Ong Siang

- Song Tiang Kay

- Tan Beng Gum

- Tan Beng Swee

- Tan Boon Chin

- Tan Chay Yan

- Tan Cheng Tuan

- Tan Chin Hoon

- Tan Choon Bock

- Tan Jiak Kim

- Tan Jiak Ngoh

- Tan Keong Saik

- Tan Kheam Hock

- Tan Kim Ching

- Tan Kim Wah

- Tan Kong Wee

- Tan Poh Neo

- Tan Soo Bin

- Tan Soo Guan

- Tan Soo Jin

- Tan Teck Guan

- Tan Yeok Nee

- Tan Yong Siak

- Tay Geok Teat

- Tay Ho Swee

- Tay Sek Tin

- Tchan Chun Fook

- Teo Hoo Lye

- Teo Lee

- Teo Teow Peng

- Thong Siong Lim

- Wan Eng Kiat

- Wee Ah Hood

- Wee Bin

- Wee Boon Teck

- Wee Guat Kim

- Wee Kim Yam

- Wee Swee Teow

- Wong Ah Fook

- Wong Siew Qui

- Wong Tuan Keng

- Yeo Swee Hee

- Yow Ngan Pan

Tuesday, 8 January 2013

Lim Leack 林烈

|

| Lim Leack |

Lim Leack or Lim Liak was born in 1804 in China with ancestry in Jingli (鏡里). He migrated to Straits Settlements in 1825. In his early time he commenced general trading under the firm Chop Hiap Chin, in which engaged principally in tin and tapioca.

In 1824, Singapore was officially established as a British Crown Colony, eyeing on the business opportunity in the new colony, Lim Leack moved there and co-founded a well-known firm, Messrs. Leack, Chin Seng & Co. The company's early founders were Lim Leack and Tan Chin Seng (son of Tan Oh Lee). It was later joined by Chee Yam Chuan. The Messrs. Leack, Chin Seng & Co., supplied various Chinese food and stuffs to the early Chinese immigrants, and was then known in Singapore as the single largest importer of goods from China. In which, stood on par with Wee Bin & Co. and Yap Whatt & Co. The firm was located at No. 29 Market Street, Singapore.

In 1851, in partnership with a prominent Straits Chinese merchant, Tan Chin Seng, they opened a branch of Leack, Chin Seng & Co. in Malacca engaged in logistic and steamship. Apart from this, the firm in Malacca was also an exporter of tin and tapioca to China. However, in engaging the business in China, Leack, Chin Seng & Co., represented itself as a British trading company by raising the Union Jack in their vessels.

Lim Leack also had the interest in property investment, in 1828 he bought three land lots in Singapore. In 1855, he purchased a 9-acre land at Tiong Bahru from the British East India Company and left it for his descendants. The land was later claimed by the Singapore government for development in 1927.

Lim Leack also had the interest in property investment, in 1828 he bought three land lots in Singapore. In 1855, he purchased a 9-acre land at Tiong Bahru from the British East India Company and left it for his descendants. The land was later claimed by the Singapore government for development in 1927.

Lim Leack's family was also known for their staunch support to Tengku Kudin during the civil war in Selangor (1867 - 1874). The relation between the Lim family with the local Malay elites is an exemplary of early social and political engagements of different ethnics in the then Malaya. However, this formation is mainly driven for the purpose of ensuring continuous economy monopolization. In which, the Lim family had the interest in tin mining concession in Selangor.

When Lim Leack died on 22 August 1875 in Hong Kong, his eldest son Lim Tek Hee (also spelled as Lim Teck Ghee) took over his business interests and inherited a considerable amount of his wealth under the Estate of Lim Leack dated on 28 June 1863.

The contributions of Lim Leack towards the economy growth of early Singapore's foundation was considered invaluable. In 1941, Lim Liak Street in Tiong Bahru Estate, Singapore was named in honour of him.

Wife:

1. Yeo Im Neo (d. 1887)

Sons:

1. Lim Teck Ghee (d. 1892) married Tan Poh Neo (1839 - 1910)

2. Lim Teck Whee (d. 1883) married Wee Watt Neo (1842-1924)

3. Lim Teck Chiang

4. Lim Tang Hun (adopted) married Wee Hoon Neo

Daughters:

1. Lim Lan Neo

Grandchildren:

1. Lim Chan Sin son of Lim Teck Whee

2. Lim Chan Siew (1877-1931) son of Lim Teck Whee

Great Grandchildren:

1. Lim Chin Chye (1896-1955) son of Lim Chan Siew

2. Lim Eng Chiang

3. Lim Eng Hock

4. Lim Eng Chye

5. Lim Ong Seng

6. Lim Teo Gek Neo

Great Great Grandchildren

1. Lim Bock Chwee

Revisions:

1st revision on 15 January 2013, with family information from Mr Lim Soon Hoe.

2nd revision on 23 January 2013 on Lim Leack's business sketch.

3rd revision on 18 August 2013 on the descendants.

Note: This article is an ongoing research with S.H. Lim. The contents may be altered from time to time.

Tags:

chee yam chuan,

chop Hiap Chin,

Klang Civil War,

Leack Chin Seng and Co,

Lim Leack,

Lim Liak,

Lim Teck Ghee,

Lim Tek Hee,

Malacca,

Selangor,

Singapore,

Tan Chin Seng,

Tengku Kudin,

Tiong Bahru

Wednesday, 2 January 2013

Khoo Cheng Lim 邱清林

Khoo Cheng Lim was born in 1808 in Fujian, China to Khoo Wat Seng. Khoo Wat Seng was among the early Chinese settlers in Penang and was the co-founders of the Khoo family clan temple, Ee Kok Tong in 1835 (later known as Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi).

Khoo Cheng Lim who was Khoo Wat Seng's eldest son, was first married Lim Neo in China, in which he had two sons, Khoo Soo Chuan and Khoo Soo Teong. He later moved to Penang to join his father. In Penang, he married Koh Keng Yean (辜輕煙) daughter of Koh Kee Jin. The Koh family was a well established member in Penang and its patriarch Koh Lay Huan was the Kapitan of Penang. The marriage was arranged so as to increase the power of the Koh-Khoo families in the Straits Settlements.

Khoo Cheng Lim had four sons through Koh Keng Yean, and his youngest son, Khoo Cheow Teong was a Chinese Kapitan of Asahan, and was made a Justice of Peace by the British in Penang. Khoo Cheng Lim's youngest son through his principal wife in China, Khoo Soo Teong was born in 1883, he married Quah Neo in China and had four sons. His second son, Khoo Ban Seng later moved to Penang and worked for his uncle, Khoo Cheow Teong. Khoo Ban Seng married Yeoh Cheam Neo (d. 1939) and had a son, Khoo Ewe Aik.

Tags:

Khoo Ban Seng,

Khoo Cheow Teong,

Khoo Ewe Aik,

Khoo Kongsi,

Khoo Soo Teong,

Koh Kee Jin,

Koh Lay Huan

Saturday, 22 December 2012

China and her Overseas People

The Chinese Consulates

The formation of the Chinese Consulates in Singapore and Penang in 1877 and 1890 respectively, was primarily to serve as communication platform between the Chinese Government and the overseas Chinese. Apart from that, it was also the Chinese Government's initiative to gain support and loyalty from her wealthy overseas members.

The office of the Vice-Consul functions in various aspects and capacities. The diplomatic rule of the Chinese Vice-Consul was based in demography and geography of British Malaya. For instance, the Penang branch engaged with the Chinese affairs in Penang, Perak, Selangor, Kedah and Perlis. Whereas, the Singapore branch concerned in the area such as Johor, Malacca, Negri Sembilan, Kelantan and Terengganu.

The primitive role of the Vice-Consul was also concerned in protecting the Chinese and their business interests. However, in the early 1900s, other Chinese organisations such as the Chinese Advisory Board (1890), Chinese Chamber of Commerce, Po Leung Kuk (1885) as well as other Chinese clan associations had surged in all major towns in the British Malaya, thus the importance of the Vice-Consul had apparently ceased.

In 1891, the Vice-Consul of Singapore was promoted to the rank of Consul General for Southeast Asia. And in 1933, a Chinese Consulate was established in Kuala Lumpur and dealt with the Chinese affairs in the Federated Malay States, the engagements were mostly in civil, commercial and political affairs. In subsequent to this newly formed Consulate in Kuala Lumpur, thus, the functions of the Consuls in Singapore and Penang were ceased.

Although the function of the Chinese Consulate had relinquished many of its concerns. However, the issuance of visiting passports to the overseas Chinese still evident. These passports were permission granted to the overseas Chinese for returning to their home districts in China. In 1939, the Chinese Consul in Kuala Lumpur, Shih Shao-tseng made a new policy, by having the local Chinese associations to stand as witnesses to the applicants of passport.

List of Chinese Vice-Consuls in Penang

1890 - 1894 - Cheong Fatt Tze 張弼士 (Chang Pi-shih/Thio Tiauw Siat)

1894 - 1895 - Chang Yu Nan 張煜南 (Thio Chee Non/Chong Yit Nam/Chong Chee Non)

1895 - 1901 - Cheah Choon Seng 謝春生 (Tjia Tioen Sen)

1901 - 1907 - Leong Fee 梁輝 (Liang Pi-joo)

1907 - 1912 - Tye Kee Yoon 戴喜云 (Tai Hsin-jan)

1912 - 1930 - Tye Phey Yuen (Tai Shu-yuan)

1930 - 1931 - Yang Hsiao-tang 楊念祖

1931 - 1933 - Lu Tzu-chin 呂子勤

1933 - 1941 - Huan Yen-kai

In the first five appointed Chinese Vice-Consul in Penang, the office was held by the Hakka-origin Chinese with business interests in Southeast Asia. Most of these men were illiterate, and their connections were through family-link and business collaborations. Cheong Fatt Tze and Chang Yu Nan were cousins, and Cheah Choon Seng was a business partner with Cheong Fatt Tze, whereas Leong Fee was his son-in-law. Ironically, these leaders were not Straits Chinese or British subjects but Chinese from the Dutch East Indies and they were pro-Qing government's policies in China. Their representative in the Chinese Consulate could suggest unpopular and feudal, as most Straits Chinese were then received Western education and some had been influenced by Dr Sun Yat Sen's uprising movement against the Qing Government. In fact, there were already formed the silent community in resisting the Qing Government. Early pioneers such as Goh Say Eng, Ooi Kim Kheng, Loh Chong Huo were founders of Tongmenghui in Penang, which fight against the corrupted Qing Government. On 17 August 1900, Tan Jiak Kim, Seah Liang Seah, Dr Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang founded the Straits Chinese British Association in Singapore. Two months later, a similar branch was set up in Malacca. The Penang wing was established in 1920. This association was a pro-British movement led by the Hokkien-origin Chinese, many of their members held high government positions and recognized by the British as local Chinese leaders. They represented the Chinese in the Straits Settlements and British Malaya in the local Legislative Council and State Councils. Following with the fall of Qing Dynasty Government in 1912, the appointment of the Vice-Consul in Penang by the Republic of China were more selective-based in term of education and experience backgrounds. For instance,Yang Hsiao-tang was educated at the Kiangsu Provincial College in Suzhou and prior his appointment he had held various government positions in China. And Lu Tze-chin who acted for a short term was a capable young man graduated from the Peking Academy in 1922 and Nankai University, Tianjin in 1926. He was later appointed as the first Chinese Consul in Kuala Lumpur.

NOTE: Yang Hsiao-tang was educated at the Kiangsu Provincial College in Suzhou born in Shanghai in 1890. He was educated at the Kiangsu Provincial College in Soochow. He joined the diplomatic service as a secretary in the Bureau of Foreign Affairs at Shanghai in 1911, and later became the chief secretary and director of the Land Office of the Bureau. In 1926, he was promoted Superintendent of Customs and concurrently Commissioner of Foreign Affairs at Nanking. He was appointed Chinese Consul-general at Penang in 1930 and transferred to Shanghai as Director of Shanghai Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1931. He was also in the Land Bureau of the City Government of Shanghai Municipality.

Lu Tze-chin or Lu Tzu-chin was born in Hanyang, Hubei in 1904. He graduated from the Peking Academy in 1922 and Nankai University, Tientsin in 1926. In 1928 he passed the Diplomatic and Consular Service Examinations held by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Lu Tze-chin had held the office of Chancellor of the Chinese Consulate in Vancouver, Canada (1929), Deputy Consul in Penang (1930), Deputy Consul in Singapore (1932), and acting Vice Consul in Penang (1933).

Qing Dynasty Titles and Honours

After the collapsed of the Ming Dynasty, the Qing Dynasty Government followed the Ming's ruling structure and system. The Emperor headed the six ministries (六部), each ministry was assisted by two chancellors (尚書) and four assistant-chancellors (侍郎). The only difference in the Qing's court is the ethnic classification. Each position in the Qing's court was filled by a Manchurian (the royal family member) and a Han Chinese official whom passed the state examinations. The Manchurian functions as an overseer to his Han Chinese counterpart in performing the duty. Despite the same ranking, both wore a different official attire. In which, the Manchurians will have a small round emblem on the robes and a square emblem for the Han officials.

The Qing official attire design came with the identification of hierarchy known as the Mandarin Square (補子). This Mandarin Square distinguishes into the division of military and civilian with nine rankings (九品), each ranking has a unique emblem, the first class rank being the highest and the ninth class rank being the lowest. The Mandarin Square was first used during the Mongol rule in Yuan Dynasty, after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty, the Ming's court then adopted this official ranking system. In 1391, Emperor Hongwu decreed bird patterns on the squares should be restricted to civil officials, and animal patterns reserved for military officials. However, the Qing's court started to use this system in 1652, during the rule of Emperor Shunzhi. Below are the emblem patterns used in the division of military and civil officials:

Military

1. Qilin

2. Lion

3. Tiger - Leopard (after 1644)

4. Leopard - Tiger (after 1644)

5. Bear

6. Panther

7. Panther - Rhinoceros (after 1759)

2. Lion

3. Tiger - Leopard (after 1644)

4. Leopard - Tiger (after 1644)

5. Bear

6. Panther

7. Panther - Rhinoceros (after 1759)

8. Rhinoceros

9. Sea Horse

Civilian

1. Crane

2. Golden Pheasant

3. Peacock

4. Wild Goose

5. Silver Pheasant

6. Egret

7. Mandarin Duck

8. Quail

9. Paradise Flycatcher9. Sea Horse

Civilian

1. Crane

2. Golden Pheasant

3. Peacock

4. Wild Goose

5. Silver Pheasant

6. Egret

7. Mandarin Duck

8. Quail

The Mandarin square for the Han officials has two identical pieces, one for the chest and the other for the back, each measures 12 inches square. The Qing's official attire came in a set of dark robe, red floss-silk fringes headgear and beads. There are two type of headgear used according to the season. The summer headgear has a conical shape woven from strips of bamboo and edged with silk brocade and the winter headgear usually a black skull cap with upturned fur brim. There is also a peacock feather (hua ling) attached on the headgear, this plume is a special distinction conferred by the Emperor. A single-eye plume was conferred upon nobles and officials down to the sixth class official. On the top of the headgear there is a knob that identifies the ranking of the official. The colours of the knob also distinguish the ranks, as show in the following:

1. Royalty and Nobility wore numerous pearls

2. First class official = red ball (originally a ruby)3. Second class official = solid red ball (originally coral)

4. Third class official = translucent blue ball (originally sapphire)

5. Fourth class official = solid blue ball

6. Fifth class official = translucent white ball (originally crystal)

7. Sixth class official = solid white ball (originally mother of pearl)

8. Seventh to Ninth class official = gold or clear amber balls of various designs

In the mid 19th and early 20th centuries, the Qing's court offered numerous official titles and honours to the wealthy overseas Chinese, this honour was known by the Europeans as Mandarin of the Blue Cotton. This was for the purpose in exchange of lucrative donations and investments to fund the government's expenditure in solving famine, natural catastrophe and major infrastructure investments (such as railways, factories, mining and banking). By then, many overseas Chinese had built considerable wealth and their purchase of these honorific titles was merely to enhance their social status. Most of the wealthy Chinese merchants purchased these titles under the category of Honorary, and had no absolute ruling power as of those officials in the same rank who had passed the state examinations in China.

For instance, Khoo Seok Wan (Singapore) received his Juren 举人 title in 1894 and Chan Yap Thong (Perak) received his Xiucai 秀才 title, both lads had passed the provincial examinations in China. Unlike Cheang Hong Lim (Dao Yuan degree 道員) who had purchased numerous titles for his family in 1869 (including for his ancestors and his 11 sons), his father Cheong Sam Teow was given the title Jin Shi (进士), the highest scholar title. In between 1877 until 1912, there were 295 holders of Qing honour titles and ranks, of this figure, 5 obtained through the imperial examinations. These titles include civilian titles from First grade Guang Lu Da Fu to the lowest Ninth Grade Deng Shi Zuo Lang as listed below:

Qing's Court Civilian Degrees

1st Class Official = Guanglu Dafu 光祿大夫

2nd Class Official = Jinshi Chushen 进士出身

3rd Class Official = Tong Jinshi Chushen 同进士出身

4th Class Official = Zhong Xian Dafu 中憲大夫

5th Class Official = Fengzheng Dafu 奉政大夫

6th Class Official = Chengde Lang 承德郎

7th Class Official = Zheng Shilang 征仕郎

8th Class Official = Xiuzhi Zuolang 修職佐郎

9th Class Official = Dengshi Zuolang 登仕佐郎

|

| Cheng Hong Kok 清芳阁 in 1897, it was an elite merchants' club. Some of its members had purchased the Qing honours and showed off their mandarin robes. |

|

| Chinese community in Singapore presented the Queen Victoria statue to Sir Cecil Smith in 1889 |

|

| Khoo Cheng Teow in his Mandarin attire |

|

| Low Kim Pong 劉金榜 |

|

| Foo Choo Choon, 3rd Class Rank Civilian Official |

|

| Mei Quong Tat, 4th Class Rank Civilian Official in 1894 (Courtesy: State Library of Victoria) |

References

- Chee, L.S. (1971). The Hakka Community in Malaya, with Special Reference to Their Associations, 1801-1968. Unpublished Dissertation (M.A.). Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya

- Khoo, S.N. (2008). Sun Yat Sen in Penang. Penang: Areca Books. page 22 - 23

- Tan, K.H. (2007). The Chinese in Penang: A Pictorial History. Penang: Areca Books. page 122

- Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore. London: John Murray

- Ramsay, C. (2007). Days Gone by: Growing Up in Penang. Penang: Areca Books. page 23

- The Straits Times, 4 October 1933, Page 12

- Ministry of Interior National Government of China. (1936). Who's Who in China: Biographies of Chinese Leaders 5th Edition. Shanghai: The China Weekly Review. page 181, 269 - 270

- Reynolds, D.R. (1995). China, 1895-1912 State Sponsored Reforms and China's Late-Qing Revolution, 28(3-4)

- Yen, C.H. (Sept. 1970). Ch'ing's Sale of Honours and the Chinese Leadership in Singapore and Malaya (1877-1912). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 20-32

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)